History is replete with squandered opportunities. The challenge for those in power is to assess in real time the risks of missing these moments. I had a sense back in 2009 when I was traveling to Zurich to sign an agreement with the government of Armenia that we were heading towards such a critical juncture.

The agreement would normalise Turkey-Armenia relations and have a significant and positive impact on the whole of the Caucasus. Some unexpected difficulties threatened to derail the whole process at the last moment, and had I been able to share my thoughts at the time I would have underscored the same principles set out last week by Prime Minister Erdoğan in his historic message on the events of 1915, concerning the relocation of the Ottoman Armenians. With this in mind, I believe we now have the opportunity to recapture the engagement and conciliation that eluded us in 2009.

Relations between Turks and Armenians date back centuries. As the Ottoman empire expanded, Turks and Armenians interacted in a multitude of ways. Armenians were among the best integrated communities in terms of enriching the social, cultural, economic and political life of the empire, and added untold value to the empire’s development throughout cycles of war and peace.

The influence of Ottoman Armenians in intellectual and artistic circles cannot be overstated. Works of many Ottoman musicians might not have survived had not the Armenian musician Hamparsum Limoncuyan introduced a style of solfége musical teaching. Tatyos Efendi, Bimençe, and Gomitas are all well-known classical Armenian music composers who also made outstanding contributions. Edgar Manas, another Armenian, was one of the composers of the Turkish national anthem.

Ottoman architecture of the 19th century was marked by works commissioned by the Ottoman sultans to Armenian architects, most notably builders of the Balyan family. Well known landmarks of Istanbul, such as the imperial palaces of Dolmabahçe and Beylerbeyi, are attributed to the Balyans, as are several significant mosques along the Bosphorus. One of my predecessors, Gabriel Noradunkyan, served as foreign minister of the Ottoman Empire from 1912-13 and was a prominent Armenian figure in international affairs.

The power of the Ottoman empire declined continuously in the 19th century. The loss of the Balkan provinces was a striking defeat which resulted in mass atrocities, expulsion and the deportation of Ottoman Muslims. A series of ethnic cleansings in the Balkans pushed millions eastward, transforming the demographic structure of Anatolia and leading to the destabilisation and deterioration of communal relations there as well. Approximately 5 million Ottoman citizens were driven away from their ancestral homes in the Balkans, the Caucasus and Anatolia. While much of western history tells of the suffering of the dispossessed and dead Ottoman Christians, the colossal sufferings of Ottoman Muslims remains largely unknown outside of Turkey.

It is an undeniable fact that the Armenians suffered greatly in the same period. The consequences of the relocation of the large part of the Armenian community are unacceptable and inhuman.

What is also true is that the dispute over why and how the Armenian tragedy happened, sadly, continues to distress Turks and Armenians today. Communal and national memories of a pain, suffering, deprivation and monumental loss of life continue to keep the Armenian and Turkish peoples apart. Competing and seemingly irreconcilable narratives on the 1915 events prevent the healing of this trauma. What we share is a “common pain” inherited from our grandparents.

National memories are important. However, could Turkish and Armenian narratives not come closer together, could a “just memory” not emerge? Believing this can happen, Turkey proposed a joint commission composed of Turkish and Armenian historians to study the events of 1915. The findings of the commission, if established, would bring about a better understanding of this tragic period and hopefully help to normalise our relationship.

Offering condolences to the descendants of Ottoman Armenians with compassion and respect is a duty of humanity. An almost century-long confrontation has proved that we cannot solve the problem unless we start listening to and understanding each other. We must also learn to respect, without comparing sufferings and without categorising them.

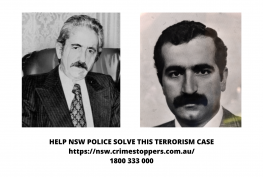

Addressing my ambassadors few years ago, I called for a change to Turkey’s “concept of diaspora”. I told them that all diasporas with roots in Anatolia – including the Armenian diaspora – are our diaspora too, and should be treated as such with open arms. Though many of our diplomats still mourned their friends and colleagues taken by terrorists from Asala (the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia), I am proud to say that they welcomed these instructions with enthusiasm and without any wish for revenge. They knew that we would better cherish the memories of the dead if we could bury hatred altogether.

Everybody can become partners in this, and for our own part we see clearly that unless justice is done for others it will not be done for us.

I appeal to everyone to seize this moment, and to join us to reconstruct a better future for Turkish-Armenian relations. The statement by Prime Minister Erdoğan is an unprecedented and courageous step taken in this direction. I believe now is the time to invest in this relationship. But we can only succeed if this endeavour is embraced by a wider constituency intent on reconciliation. Turkey stands ready.

Ahmet Davutoglu