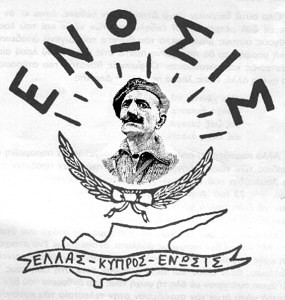

Much has been said about the Turkish intervention in Cyprus in 1974. Many Greek lobby groups have portrayed the Turkish Army as some sort of bloodthirsty invading force. The truth, as is spelled out in the article, below, is that Greek nationalists had for years been running a campaign of terror, violence, and discrimination, aimed at “ethnically cleansing” the previously peaceful island of its Turkish population.

Turks had been living in Cyprus for 500 years and had mostly lived in complete peace and harmony with their Greek neighbours. Fascist sentiment would not allow this, and, had it not been for the timely arrival of the Turkish Army, we would have witnessed one of the century’s most devastating acts of genocide – the annihilation of any non-Greek (ie Turkish) element in Cyprus. You don’t have to take our word for it, read what the Greek Cypriot political and military leaders were saying for themselves.

The plan to annihilate the Turkish population was no secret. Yet today, lobby groups bend over backwards to try to condemn Turkish Cypriots as somehow responsible. We are thankful that the Republic of Turkey was willing to step in to prevent the planned massacres, and we hope that saner voices on the Greek side will prevail, allowing Cyprus to once again unite, as a Federation, guaranteeing the existence of Cyprus as an independent nation, with equal rights for ethnic groups.

The Turkish North has repeatedly voted to reconcile, and become one nation. It is the Greek South, post acceptence into the EU that has rejected the proposals. These facts, and others, are summarised in the following piece, actually a set of written submissions to strike out an action on this issue in a US Court Case.

Above all, we wish for nothing other than a just an fair peace for all the people of the beautiful island of Cyprus.